Tomioka Silk Factory

Our main reason for coming to Takasaki was to visit the Tomioka Silk Factory. It was Japan’s first modern silk factory, established in 1872; it operated until 1987; and in 2014 it was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the first Japanese factory, we believe, to be so designated.

Getting to Tomioka is easy once you know how. The trick was to know that the destination is not Tomioka, but Jōshū-Tomioka Railway station. It’s on one of Japan’s private railways, with the train running from Takasaki, and taking around 40 minutes. For Y22OO each, we got a return train ticket and entrance to the site. Another Y2OO each gave us an English language audio-guide, which was excellent. They do have a smartphone app, but we only have one smartphone with us for this trip, so we opted for the guide. The admission attendant was really helpful.

There weren’t many people on our train there, and we were the only ones who got off at our stop, but as we turned the last corner on our walk to the factory, we saw quite a crowd ahead of us. It was obviously a tour group as when we got to the entrance we were fast-tracked through an empty lane. Once inside, the numbers swelled more; there were several school groups there. This little village is out in “the sticks” really, but the site is clearly well-known and respected by the Japanese.

The UNESCO World Heritage listing comprises four sites, reflecting the different stages in raw silk production:

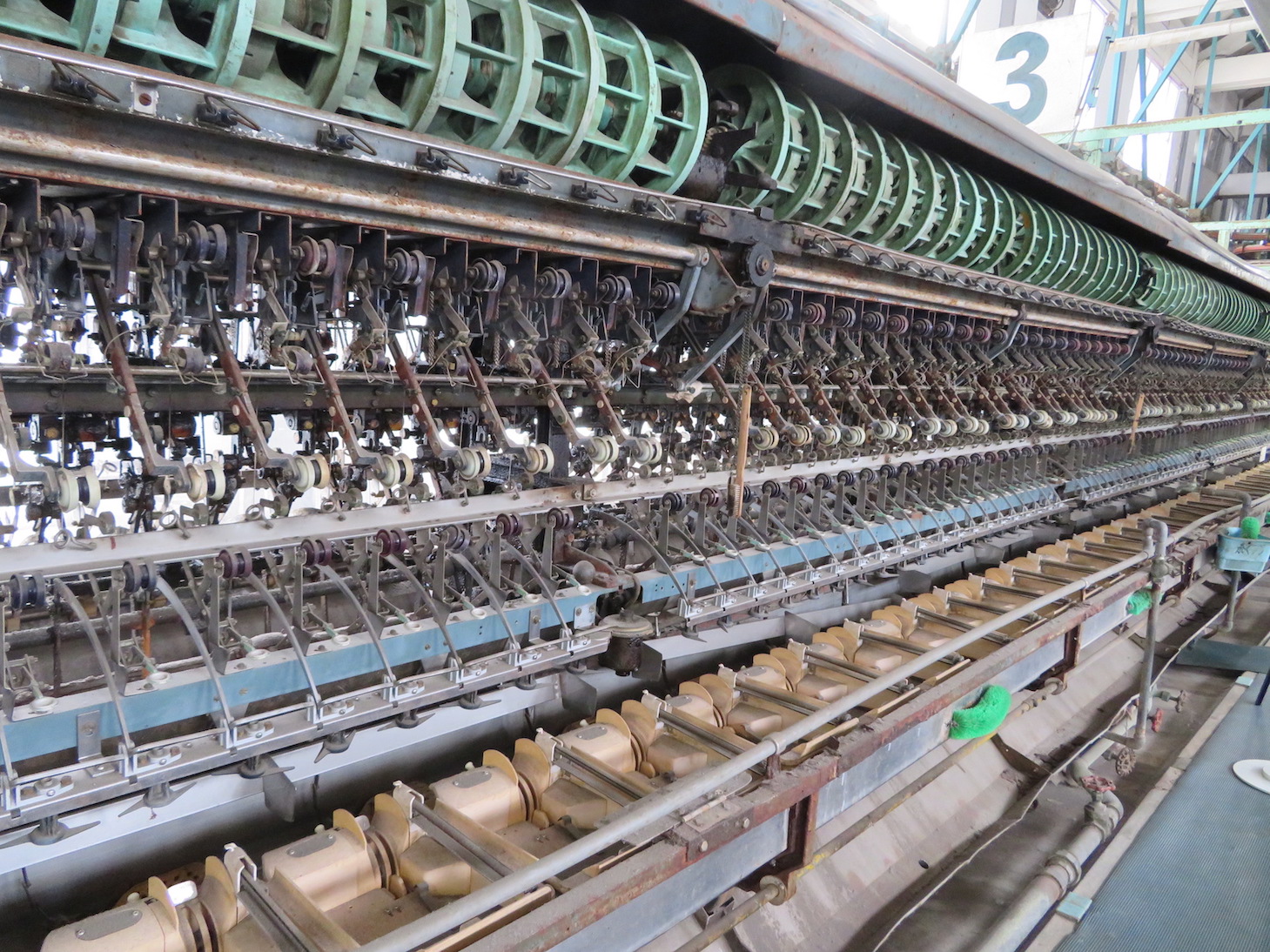

- a large raw silk reeling plant whose machinery and industrial expertise were imported from France, then further developed by the Japanese;

- an experimental farm for cocoon production;

- a school for disseminating sericulture knowledge; and

- a cold-storage facility for silkworm eggs.

Only the first, the actual mill/factory, is at Tomioka. It’s the centrepiece of the listing, and all we could visit. We found it well worthwhile.

First, a little history. The Tomioka Silk Mill (aka Factory) functioned as a model for modern silk milling in the country during the Meiji Period, when Japan was striving in all areas of life and culture to “catch up” with the West. This mill played an important role in making the textile industry Japan’s most important industry for several decades, and thus sustaining the growth of Japan’s economy. It was not only Japan’s most modern silk reeling factory, but was also one of the world’s largest at the time of its construction.

It was established by the national government, with a major aim being for it to be a model facility. The government invited French advisers to help develop it, because France was superior in reeling silk. Consequently, it was Frenchman Paul Brunat, its first director, who researched suitable locations for a silk mill in the Kantō region. He selected the Tomioka site for various reasons including that there was:

- a large space available for the factory complex (large spaces being rare in Japan)

- already quality sericulture in the region

- already some irrigation infrastructure

I love hearing the reasons for why things happen when and where they do, so found this sort of information from the audio-guide excellent.

The end result was that Tomioka established a good reputation overseas for its high quality. Interestingly, though, it struggled to make money. The government privatised it (ha!)) in 1893. It was sold to another company in 1902, and then again in 1939 to Katakura Industries which was Japan’s largest silk reeling company. They operated it until 1987, when they closed it.

Now for some of the other things that I, or we (depending), particularly enjoyed:

- the live demonstration of silk reeling: fascinating to Len who loves understanding hands-on skills and to me because of my memories of struggling to “reel” silk in my own childhood silkworm raising days!

- the European influence on the architecture, with Japanese input, particularly in construction techniques

- the fact that women were recruited from all over Japan, partly to be trained to take the latest silk reeling techniques back to their home towns. This resulted in other silk mills being established throughout the country using the Tomioka model.

- the fact that the workers’ conditions were enlightened for the times: they averaged 8 hours a day (more in summer and less in winter, according to the light); they had morning break and a one-hour lunch break; they had Sundays and other holidays off; and gradually were given training and education in other skills and subjects.

- the story of Tomioka Nikki (or the Tomioka diary): it was written by Ei Wada/Wada Ei (1857-1929), a 15-year-old recruited mill-hand who returned to her hometown in Nagano where she helped establish the Rokkosha Silk Mill. When she was 50, she vividly described her experiences as a mill hand, creating an excellent primary resource for understanding both the techniques and practices, as well as the lives and experiences of the young women working there. I think there is an English translation but it’s not available, as far as I can tell, in e-version. The audio-guide included a few quotes from it.

There is a funny story about recruiting the women. It didn’t go well at the start. Apparently, the French had been spotted drinking red wine, and the rumour started that they drank blood! Potential women recruits were terrified. Eventually, it was sorted, partly by the mill’s head manager employing his own daughter to prove there was nothing to fear! How easy it can be to misread or misconstrue other cultures!

Lunch and wandering streets of Tomioka

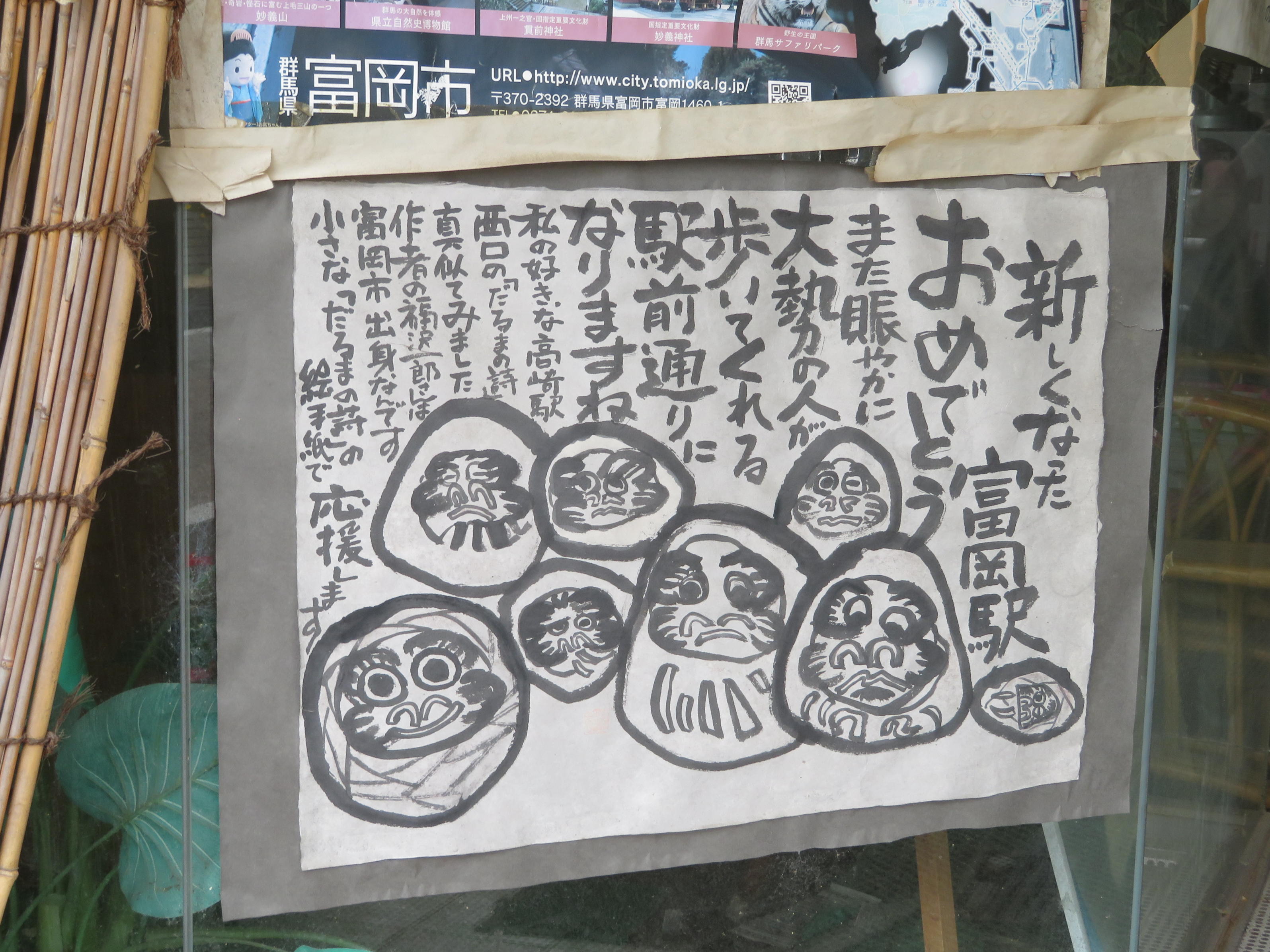

Both on the way to the factory, and after it, we enjoyed pottering around the narrow streets of Tomioka (avoiding the more tourist-focused shops right near the factory). I love looking for little details – in addition to manhole covers (!) – such as, here, the decorative art (or advertising) painted on, for want of a better description, cane blinds/mats. Images included the Daruma. We also passed a gorgeous little Matsumoto-like “karu” style warehouse, that looked beautifully maintained.

A little away from the factory, we found a basic cafe, where we each had a bowl of soba. It wasn’t fancy, but they were happy to serve us, and the meal did the job! For around Y640 each, you couldn’t complain.

Afternoon and Dinner

We got back to Takasaki around 2.30pm, having left for Tomioka around 9am. We pottered for a little while around some shops (including food shops which we always enjoy checking out); had a cuppa at a stylish little cafe called Cafe Comme Ça; and then returned to the hotel for those jobs that need to be done, like washing. This took somewhat longer than expected, because I added around 45 mins to the cycle to by inadvertently pressing a “soak” button! Oh well, this hotel’s washing machine was free – though the dryer cost – so I just occupied myself drafting this blog post!

While I was washing, drying and drafting, Len was processing videos and researching dinner. He lit upon a yakitori place called Kamikaze, which was just around the corner from our hotel. It turned out to be a more modern classy joint – so of course, the drinks were smaller but more expensive. However, I’m interested in how modern food culture is playing out in Japan, and this was an example, right down to the minimalist decor and tableware. We ordered the 7-course yakitori meal, which basically meant each of us got 7 yakitori sticks, chef’s selection. Having clarified we eat anything, we then waited. We got, all chicken of course: breast (mune), heart (hatsu or kokoro), liver (kimo or reba), gizzard (sunagimo), neck (seseri), inner breast (sasami) with some alternating spring onions (negi), and thigh (momo). Our server did her best with English translation (and I’ve done my best tracking down the Japanese names for what we had!) It was all cooked simply but beautifully. The Japanese, you might have realised, waste very little.

I started with a tiny glass (100 mls I think) of New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc – the only white by the glass, but at least it was identified – and then had 100 mls of a Gunma Prefecture Sake.

And some Stills…

And some Movies…

Click here to view today’s video clips

Today’s Challenges …

- Finding the (tucked away) private railway station platform at Takasaki station in order to go to Tomioka.

- Choosing what to eat and drink from our no-English menu lunch and dinner restaurants, and understanding the English names provided by our server at the second.

- Working out how to use a different washing machine and dryer with no English instructions.

Remember when we used to be able to buy real silk? Such a beautiful fabric, but I never see it anywhere these days.

It needed handwashing, maybe that’s why.

You’re right Lisa. It is beautiful, but the care always put me off!! I’d touch longingly and move on. Except for a silk scarf. they are easier to care for.

FASCINATING day ! 🙂 Thanks for your reportage, Mr and Mrs Gums – I was riveted (how many ts?) by it. Of course we had silkworms as kids in Perth – we had a huge and very climbable mulberry tree in our front garden, so what else ? 🙂 But all we ever did was experiment with changing the colours of the cocoons by what we fed the little things.

Isn’t it extraordinary how strong that silk is ?!

Being a dedicated washerwoman, I applaud your achievements.

I do like the Kamikaze eating place ! – yous were game. [grin]

Thanks M-R, and I thought this post was less interesting! Yes we had a mulberry tree in our Brisbane home where I had silkworms. I remember the colour thing, and also trying to reel off silk thread but couldn’t get long threads. Of course we waited for the moth to emerge so there was a hole in the cocoon! Silk factories don’t do that.

We are happy to try most foods – though I haven’t eaten much in the way of insects – yet.

For years I’ve read about how it was silk that paid for the modernization of Japan and now I’ve seen it up close thanks to you. I really enjoyed Len’s hushed commentary about silk spinning. I was also surprised at how many of your readers played with silk cocoons as children. That wasn’t a part of growing up in Oregon that’s for sure.

Oh, I’m glad I helped put the history in context Carolyn.

How interesting about silkworms. I guess it’s related to climate. You really have to have mulberry leaves for them. There’s not much else they eat. Len and his sister didn’t have them.

Fascinating! Amazing little insects able to produce such strong thread! And I wonder how and when people came to realise its potential. Those bundles of thread! How is it unraveled and woven? Ours is an amazing world filled with amazing things!

And the most amazing can be how people worked out the potential, can’t it? I agree with you. What made them think it? I suppose for all the successes there have been many things tried that did not prove to be useful?

Oops! That apostrophe in the “it’s”.

I have fixed!

The picture of the Daruma includes a famous proverb “nanakorobi yaoki“ or fall down seven times and get up eight times—the idea being to keep on trying—the Daruma always ends up back in the upright position.

I wondered if you might translate for us, Carolyn. Thanks.

I think the Daruma are supposed to but it seems to me that many/some of the souvenir ones sold have flat not round bottoms, so I think they will fall over and not get back up! That’s a shame really.